This is the first in a special three-part series exploring the women—both real and imagined—who helped shape the sci-fi and fantasy genres. Each essay highlights a creator, character, or trope that’s left its mark.

So Good She Must Be a Man

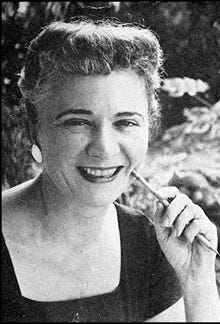

In the 1930s & 40s, Catherine Lucile Moore—better known as C.L. Moore—was writing sci-fi and fantasy stories so gripping and evocative that many readers thought they were written by a man. And while I personally think gendering authors can lead to some sticky situations, after reading Moore’s Shambleau, I know exactly what they mean. Before Ursula K. Le Guin and Octavia Butler, Moore was paving the way for women in the speculative fiction genre with strong characters and provocative plots.

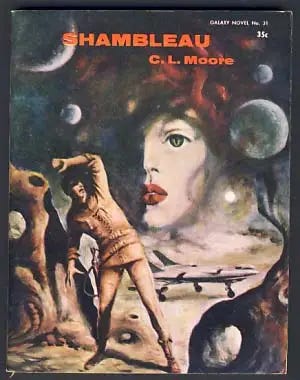

Her first professional-level story, Shambleau introduced the world to one of sci-fi’s earliest antiheroes—Northwest Smith—and helped define the genre’s early years.

Let’s dive into her legacy.

A Moment of Boredom That Changed Sci-Fi Forever

In 1933, amidst the backdrop of the Great Depression, Moore was working as a secretary when inspiration struck. She later recalled:

"I had nothing to do—but I really should’ve looked busy because jobs were hard to get! I didn’t want to appear that I wasn’t earning my daily keep! To take up time, I was practicing things on the typewriter to improve my speed… That got boring, so I began to write bits of poetry I remembered from my college courses…in particular, I was quoting a poem called 'The Haystack in the Flood.'”

One misquoted line, "A red, running figure," sparked Moore's imagination. Who was running? Why? From that moment of boredom, Shambleau, the story that would launch her career, was born.

Originally published in Weird Tales, the story starts with a Lovecraftian introspection: Man has conquered space before. You may be sure of that. A warning, actively informing the reader that the following story marries the old and the new, which is true both in plot devices and in genre. We’ll see ancient monsters haunt Mars and cowboys pilot spaceships. Past and future. Moore loops them together effortlessly. Man has conquered space before, remember?

Readers are then introduced to Northwest Smith, a rogue space adventurer—predating, it is to be noted, Han Solo by decades. When he saves a mysterious woman—Shambleau—from an angry mob, he inadvertently invites in something far more menacing. The not-quite human creature preys upon Northwest in ways that mix horror, eroticism, and adventure—a genre-bending blend that was revolutionary at the time.

For history buffs, Shambleau herself is a delightful twist on Medusa, offering both her famous freezing stare and snake-like hair but twisted in a way only science fiction is free to do. What’s better yet, Moore writes Shambleau in a way that almost makes the reader sympathize with her. She can’t help it, it’s how she is. It’s how she survives. It’s not her fault.

I found Northwest Smith just as interesting and compelling as other famous cowboy-esque, rogue heroes of science-fiction, fantasy, and even westerns. Northwest instantly reminded me of Vash the Stampede of Trigun fame and Cowboy Beebop while simultaneously harkening back to great cowboy legends like John Wayne. There is something familiar about Northwest, something replicable that Moore might have taken from westerns of her time and applied to science fiction, to much success.

Moore’s rich, psychologically driven storytelling stood apart from the pulp action of the era. Readers took note.

The Woman Behind the Mask: C.L. Moore & Henry Kuttner

Moore continued to feel the effects of her success throughout the 1930s, though by the 1940s she partnered with writer Henry Kuttner. Kuttner, a fan of Shambleau and fellow Weird Tales alum, originally wrote to Moore, not realizing she was a woman. From faux pas to love, the two were eventually married and wrote together under multiple pen names, including Lawrence O’Donnell and Lewis Padgett.

Following Kuttner’s death in 1958, Moore largely stopped writing fiction, fueling the theory that Kuttner was responsible for most of their creative works. But, according to an interview she did in 1976 with Chacal Magazine, after Kuttner’s death she was already fully immersed in writing for television and ended up taking on teaching her husband’s writing courses at USC. She was simply “dried out on science fiction.” How unfortunate for readers.

Moore would continue writing for television—most notably Maverick, a series oddly similar to Northwest Smith’s stories—until remarrying in 1963, where she ceased writing completely. Despite bowing out of the science fiction publishing community, she would go on to receive the Forry Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1973 and a Count Dracula Society Award for literature in 1977. In 1981, Moore was honored as the final recipient of the Gandalf Grandmaster Award and received the World Fantasy Lifetime Achievement Award. Posthumously, she was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 1998 and received the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award in 2004.

Why C.L. Moore Still Matters

Moore’s work influenced generations of sci-fi and fantasy authors. As one of the only female voices amongst the science fiction community in the 1930s, she laid the foundation for authors like Le Guin and Vonda N. McIntyre. The space cowboy character she created in Northwest Smith would go on to be replicated many times over in future science fiction novels, series, and movies. Her work and the way it combined sci-fi, fantasy, and horror paved the way for future female storytellers of speculative fiction.

Her characters—like Jirel of Joiry, one of the first female sword-and-sorcery protagonists—helped break ground for women in genre fiction. Without Jirel, we may not have George R. R. Martin’s Brienne of Tarth. Or within my own work, I would have no reference for Cecelia or Mara—my own heroines walking a fine line between steel and female empathy.

Moore matters because she planted the seed in the early rise of science fiction and fantasy that women can write genre fiction, too. That we can pull from our sources and create new, exciting stories and characters that don’t have to fit into a preconceived mold. Her stories serve to inspire modern female speculative fiction authors to push boundaries, not take no for an answer, and to write what you want to read.

Read Shambleau for Free

If you’d like to read the story that launched C.L. Moore’s career, Shambleau is available for free on Archive.org:

📖 Read Shambleau here

For more of Moore’s work, check out:

"Black God's Kiss" – Introduces Jirel of Joiry, an early warrior-queen protagonist.

The Best of C.L. Moore – A collection of her most famous stories.

Final Thoughts

Pioneers aren’t always loud—but they pave the way just the same. Moore’s name may not be as widely known as Asimov’s, but her impact on sci-fi and fantasy is unquestionable. I will no longer be able to engage in those famed futuristic cowboys without remembering Northwest first. And I’ll certainly peer into the past when writing science fiction, because Moore’s work reminds us that time is cyclical. What was once past could easily be revived. Why can’t Greek horrors appear in space? What if they were there first?

We’ve conquered space before, remember?

Your Turn

What do you think? Have you read any of Moore’s work? Let me know in the comments, or reply with your favorite overlooked sci-fi/fantasy writers!

If this story intrigued you, consider sharing this newsletter with a friend who appreciates the nuances of science fiction and fantasy. Let's continue the conversation about the stories that shape us.

Sources & Further Reading

Next Up in Women of Wonder

Next time on Women of Wonder, we’ll dive into a short story that’s haunted me for years—written by a complicated figure in genre history: The Wind People by Marion Zimmer Bradley.